Geneva, 19 June — The World Health Organization (WHO) today released its first-ever global guideline on the management of sickle cell disease (SCD) during pregnancy, addressing a critical and growing health challenge that can have life-threatening consequences for both women and babies.

SCD is a group of inherited blood disorders characterized by abnormally shaped red blood cells that resemble crescents or sickles. These cells can block blood flow, causing severe anaemia, episodes of severe pain, recurrent infections, as well as medical emergencies like strokes, sepsis or organ failures.

Health risks associated with SCD intensify during pregnancy, due to heightened demands on the body’s oxygen and nutrient supply. Women with SCD face a 4- to 11-fold higher likelihood of maternal death than those without. They are more likely to experience obstetric complications like pre-eclampsia, while their babies are at greater risk of stillbirth or being born early or small.

“With quality health care, women with inherited blood disorders like sickle cell disease can have safe and healthy pregnancies and births,” said Dr Pascale Allotey, Director for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research at WHO and the United Nations’ Special Programme for Human Reproduction (HRP). “This new guideline aims to improve pregnancy outcomes for those affected. With sickle cell on the rise, more investment is urgently needed to expand access to evidence-based treatments during pregnancy as well as diagnosis and information about this neglected disease.”

There are around 7.7 million people living with SCD worldwide – a figure that has increased by over 40% since 2000. SCD is estimated to cause over 375 000 deaths each year. The disease is most prevalent in malaria-endemic regions, particularly sub-Saharan Africa–which accounts for around 8 in 10 cases–as well as parts of the Middle East, the Caribbean, and South Asia. With population movements and improvements in life expectancy, the sickle cell gene is also becoming more widespread globally, meaning more maternity care providers need to know how to manage the disease.

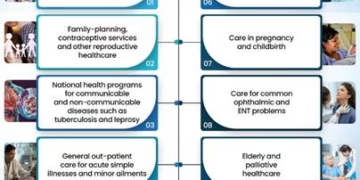

Until now, clinical guidance for managing SCD in pregnancy has largely drawn on protocols from high-income countries. WHO’s new guideline aims to provide evidence-based recommendations that are also relevant for low- and middle-income settings, where most cases and deaths from the disease occur. Accordingly, the guideline includes over 20 recommendations spanning:

- Folic acid and iron supplementation, including adjustments for malaria-endemic areas;

- Management of sickle cell crises and pain relief;

- Prevention of infections and blood clots;

- Use of prophylactic blood transfusions; and

- Additional monitoring of the woman and the baby’s health throughout pregnancy.

Critically, the guideline highlights the need for respectful, individualized care, adapted according to women’s unique needs, medical histories and preferences. It also addresses the importance of tackling stigma and discrimination within healthcare settings, which can be a major challenge for people with SCD in several countries around the world.

“It’s essential that women with sickle cell disease can discuss their care options early in pregnancy—or ideally before—with knowledgeable providers,” said Dr Doris Chou, Medical Officer and lead author of the guideline. “This supports informed decisions about any treatment options to continue or adopt, as well as agree on ways of handling potential complications, so as to optimize outcomes for the woman, her pregnancy, and her baby.”

Given the complex nature of these disorders, if a pregnant woman has SCD, the guideline notes the importance of involving skilled and knowledgeable personnel in her care team. These may include specialists like haemotologists as well as midwives, paediatricians and obstetrician-gynecologists who provide services for reproductive and newborn health.

SCD is a neglected health condition that remains considerably under-funded and under-researched, despite its growing prevalence worldwide. While treatment options are improving for the general population, the guideline underscores the urgent need for more research into the safety and efficacy of SCD treatments for pregnant and breastfeeding women – populations that have historically been excluded from clinical trials.

This publication is the first in a new WHO series on managing noncommunicable diseases in pregnancy. Future guidelines will address cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, respiratory diseases, mental health disorders and substance use. Chronic diseases are increasingly recognized as major contributors to maternal and newborn deaths and ill health.